Loft Living at Whitehall Mill

Publication:Athens Magazine

When modern architecture came to Athens in the early 1900’s it arrived in buildings so modest that for years people passed them by without much thought. But with a new century just around the corner, it is time to take a closer look.

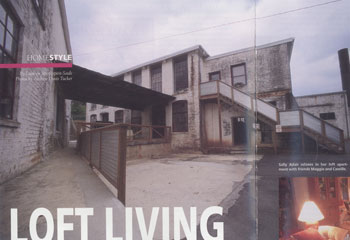

While most visitors and many residents focus on the charm of Athens’ historic districts, they are learning to expand their scope to the city’s perimeter and to renovations such that of the old Thomas Textile mill, previously Whitehall Mill, built circa 1860. Located off Whitehall Road next to the Oconee River, which originally provided power for the mill, the sprawling brick buildings are now trendy loft-style apartments.

|

| Sally Adair relaxes

in her loft apartment with friends Maggie and Camille. |

The secluded apartments attracted Oglethorpe County High School teacher and artist Sally Adair immediately. She moved into the first loft last February and was the sole inhabitant of the complex for several months.

“It was sort of weird at first, being here all by myself. But I loved it. I fell in love with the place right away. I said to myself, ‘Doesn’t anyone else see what I see?’ I came here to have a studio to work in; I wasn’t interested in living here at first.”

The blend of cement floors and ancient brick walls that greet visitors as they enter her foyer is softened by age and the warmth of colorful woven rugs and several paintings by Sally. The light from eight-foot-tall casement windows reflects into an efficient kitchen (with a courtyard view). An adjoining bedroom is brightened from a skylight in a 30-foot ceiling overlooking a staircase.

The wood beams that were cut out to make the skylight have been recycled into steps that lead to the second floor studio. Creative decorating and hanging potted plants to take the focus away from exposed pipes and other industrial effects, giving the unit a cozy warmth. Sally says her loft is an artist’s dream with all the light and space.

“This place is so unique that it has inspired me to draw and paint different buildings and sites around here.” Her staircase wall is a gallery of paintings and drawings of various buildings and industrial machinery.

“Having all this space ruins you from ever living in a non-loft environment again. An added plus is that we have a community here; we take care of each other. It’s sort of like a village,” Adair says.

The renovation of the abandoned mill site, by Miller Gellman Development of Atlanta has resulted in 36 loft-style units suitable for residences and businesses. The buildings had been abandoned for 10 years, but it took Jerry Miller and Bruce Gallman only six months to bring the complex back to life once construction began.

“We received our certificate of temporary occupancy from Clarke County in December [1997],” says Miller. “It had taken us about a year of working with people in the neighborhood to educate them as to what we wanted to do then another year to got through the zoning process. Athens is politically cognizant of neighborhood opinion, and we didn’t want to go into something with an adversarial relationship. We wanted it to be a partnership.”

The

process began with getting the site listed on the National Register of

Historic Places. Then they had to design the plans according to the secretary

of interior’s

guidelines to maintain the historical integrity of the building. Miller

says that for every dollar spent on this type of project, 20 cents comes

back to them as a tax credit. The Whitehall Mill project cost over $2.8

million, including the price of the property.

The

process began with getting the site listed on the National Register of

Historic Places. Then they had to design the plans according to the secretary

of interior’s

guidelines to maintain the historical integrity of the building. Miller

says that for every dollar spent on this type of project, 20 cents comes

back to them as a tax credit. The Whitehall Mill project cost over $2.8

million, including the price of the property.

“We shopped around and selected this site because it had more character than any other place we looked at, including the natural setting. There isn’t another place like this one; it is surrounded by 50 ft bluffs and rolling river shoals. Plus the former owner, Thomas Swartz, kept the mill building in fairly good condition,” Miller explains.

The Whitehall Mill Lofts are situated in a natural hollow along the North Oconee River, adding to their attraction. Of the is buildings located in the complex, two have already been renovated and are occupied.

Each loft is individual because it is designed to work with the original architecture: i.e., high vaulted ceilings, outdoor staircases to upper decks, plaster and brick walls, knotty pine paneling, floor to ceiling windows and access to courtyards to name a few details.

The tenants have used their talents to turn the outside into a natural showcase by creating courtyards and deck patios with flowering plants, hanging vines, potted trees and herbal gardens.

All but two units are currently occupied. Lease pricing begins at $700 per month and runs to more than $1000 per month, depending on the building, level, and view. Every loft has a view of the river.

Plans for rehabilitating the remaining buildings include creating more loft units for businesses and a restaurant.

Julie Morgan, historic preservation planner for the Athens-Clarke County Planning Department, says it is now a trend to turn commercial space into living space, as has been happening for several years in downtown Athens near the University of Georgia.

“We’re seeing a lot of second-floor activity down there for a lot of wonderful reasons. For one thing, the buildings are flexible, with their large open spaces making them attractive for conversions, and another [reason] is their convenience.”

Morgan continues: “I’m glad that developers are now looking at the perimeter industrial sites around Athens. I think that the renovation of the Thomas Textile Mill will invite more attention to other abandoned mills and factories.”

Miller and Gallman have been in partnership for three years, specializing in historic renovations. Gallman began his career in renovation in 1983 with the old Swift Co. Meatpacking plant in Atlanta’s Castlebury Square, which he filed as an historic district. That community has had several more renovations since then. Miller began his work in historic renovation in 1984 with the old Healy Building in downtown Atlanta.

“Most loft people come in to stay because they become accustomed to the space, volume and uniqueness. I like to see them customize it and make it their own. These type units are a blank canvas for residents to be creative once they move in,” Gallman says.

He adds that historic renovation can be difficult sometimes for contractors because of unforeseen problems that have to be solved quickly in order to keep the project on schedule. On the other hand, contractors can take advantage of materials that become available because of the alterations.

“An example is what we did with the staircase design for our loft apartments here at Whitehall Mill.” Gallman explains. “In keeping with the historic appearance and structure, we were able to construct the steps by recycling the wood from the ceiling beams that were cut out for skylights.

“We take the approach that if anything has character, we keep it. We have kept everything natural here at Whitehall. Nature has given us more of a helping hand here, too, with the environmental surroundings.” Gallman adds.

Although the American ideal is a house and an acre of land, the Bohemian and cosmopolitan blend of a loft is alluring to some but not all. The loft type dwelling is different from a standard apartment, although the living style is similar. A traditional apartment is designed to the conformity of an architectural blueprint, and a loft is designed to fit into an existing industrial structure.

Miller says that his company was more or less put under a microscope by Athens-Clarke County authorities during their inspections because the Whitehall renovation was untraditional in some ways, such as the recycling of materials and working around the design of existing structures.

“What we’ve done here will probably set a precedent for other developers in renovation. We’ve done everything we can in keeping with the local and historic building codes, from concealing noise levels to providing a safe environment,” Miller says.

“But in this type of dwelling, it’s expected that there will be some nuisances, [such] as sounds that reverberate through the industrial pipes overhead. Some people find these types of noises comforting, others don’t. We try to put [in] additional buffering, but loft living is not a traditional type of living environment.”

Miller says that loft life targets people between 25 and 45 with no children, as well as some seniors: “Anyone who wants to live in a creative environment with a creative lifestyle. These are the people who will overlook any minor nuisances to enjoy all of the amenities that come with loft living."

The mill was originally designed in 1829 by John White of Antrim County, Ireland. White and his wife Janet Richards designed a manor house nearby called White Hall, that served as the residence for the family until 1892, when they built a new Gothic/Victorian-style mansion. This house is now owned by the University of Georgia School of Forest Resources.

The mill changed ownership several times and was known by several names: Athens Manufacturing Co., Georgia Factory, Georgia Manufacturing Co., and finally Thomas Textile Mill. It was one of the first three mills built in Georgia, marking Athen’s importance in early industrial history.

Early reports of the mill show that it employed from 80 to 100 persons and about an equal number of whites and blacks. The early view of mill life is documented as being dismal, with the white families living in log huts clustered about the establishment on the river’s bank and the blacks (who were leased to the mill by their owners) living in huts nearby. The lifespan of these mill workers was short due to diseases fostered by unhealthy conditions.

Many died from fevers caused by malaria. The mill continued to progress in spite of these setbacks and led to the growth of the village, which became established as the town of Whitehall on October 15, 1891. Whitehall was known as a “round town,” due to the common development of manufacturing villages around the circumference of city factories.

The loft-style renovation concept being implemented to recycle abandoned cotton mills, warehouses and other large buildings into apartments and business spaces is new to Northeast Georgia but has been popular for some time across the South. Other Atlanta developers have ventured into numerous multimillion-dollar renovations in the historic warehouse district known as Cabbagetown over the past decade, creating fashionable restaurants and business habitats.

Robert Silver spent an estimated $10.8 million in the conversion of the old Bass High School in Little Five Points to Bass Lofts luxury apartments. And developers in Cherokee County are investing millions to transform the old Canton Textile Mill, a 400,000 square-foot, three-story red brick warehouse, into retail space and loft apartments.

In New Orleans, a 100-year-old abandoned brewery has been converted into a shopping mall along the waterfront and is now a major tourist attraction. And the century old Maginnis Cotton Mill in the New Orleans warehouse district now has luxury penthouse condominiums.

The same type of recycling is also being seen in North and South Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee and Virginia.

“I have renovated a tobacco warehouse in Richmond, built back in the 1860’s,” says Richie Rickman, project superintendent for Whiting-Turner Contractor of Atlanta. “We were able to preserve the entire block-long, six-story building, including its four-inch thick plank flooring, beams, columns, 20-inch solid-brick walls and exterior brick.

“The interior was divided into unique lofts with exposed [structural elements], a new feature unlike common apartments. This development brought more affluent residents to a previously low-income area.”

Rickman adds that this kind of popular development can be cost effective for developers and also save them the grief of resistance from local historic preservationists who want to save the persona of an old community. The marriage of old and new seems to be good business.

In cost comparisons between renovating the old versus building new, Jerry Miller says that, in the case of Thomas Textile Mill, it came about the same because they recycled everything that they had to alter or take out back into the units to maintain the integrity of the building.

“This is much better though and couldn’t be duplicated. I wouldn’t even know how to estimate a replication of something like this. You can’t duplicate this type of masonry, log beams, thick floor planking, etc. It has a uniqueness all of its own. There isn’t a replacement value–you can’t get this kind of stuff anymore.”

Miller and Gallman believe that the popularity of their development at Whitehall will accelerate the local community’s willingness to begin more refurbishing. “It would have probably happened eventually, but I feel that our work here will speed things up. People are looking at mill communities now–the mill houses, because of the village type atmosphere,” Miller says.

Julie Morgan says that there are several other potential sites for conversion of abandoned mills in the Athens perimeter. “I believe this type of conversion is a national trend because of the aesthetic beauty of the surrounding environments–with water fronts–of these factories, making them more popular for developers to come in. Conversions like the Whitehall Mill Lofts show that it is trickling into Athens,” she says.

Perhaps the new makeovers will create a new perception of these once neglected and unadorned industrial buildings and make them friendly sites in the community. One thing is certain, the Whitehall Mill is here for another century.

Laureen Stronspirit-Sauls is a freelance writer living in Commerce.

Photography by Andrew Davis Tucker